Are Three-Pointers Worth Too Much?

A little bit of silliness and numbers.

The abundance of three point shooting can be credited (maybe angrily) to analytics people, who figured out the expected value of the shot was higher than a long two pointer given good spacing and shooters.

The process was gradual, but many teams now adopt the pace and space methodology, resulting in newer archetypes like stretch bigs and 3&D wings, while freeing certain smaller players from duties like running the offense when they can play off the ball more.

Personally, I enjoy the modern era of basketball - even if I do think it gets repetitive at times. There’s an element of nostalgia rooted in the claims of “analytics has ruined the game” and “bring back the long two”. More than just nostalgia though, there is a misunderstanding of how much value the three pointer gives, even at longer distances.

Adjusting the Court:

I thought though, about other ways that the NBA could look at the issue. Kirk Goldsberry, the author of SprawlBall, took an approach to reshaping the line and the court in its entirety for an ESPN column a few years ago. I will show some of the diagrams he drew below.

The data-driven three point line comes out of an approach to make all three-pointers have the expected value of one point. You would try to find where players made 33.333% of their threes.

The next approach is trying to get rid of the short corner three. As described before, corner threes are from a smaller distance, and players actually made 39.58% of their threes from that area in 2017-18.

These are both interesting approaches - but both would result in an odd geometry on the floor. In addition, trying to change the dimensions on the court is like playing whack-a-mole. If I adjusted the three-point line so that shots behind roughly 26 feet were the only ones equal to three points, that would result in some more old-school basketball for a couple seasons, but with enough offseasons, we would have an abundance of shooters back on every NBA roster, this time shooting from farther. This would also result in a more spacing, meaning more scoring per possession eventually.

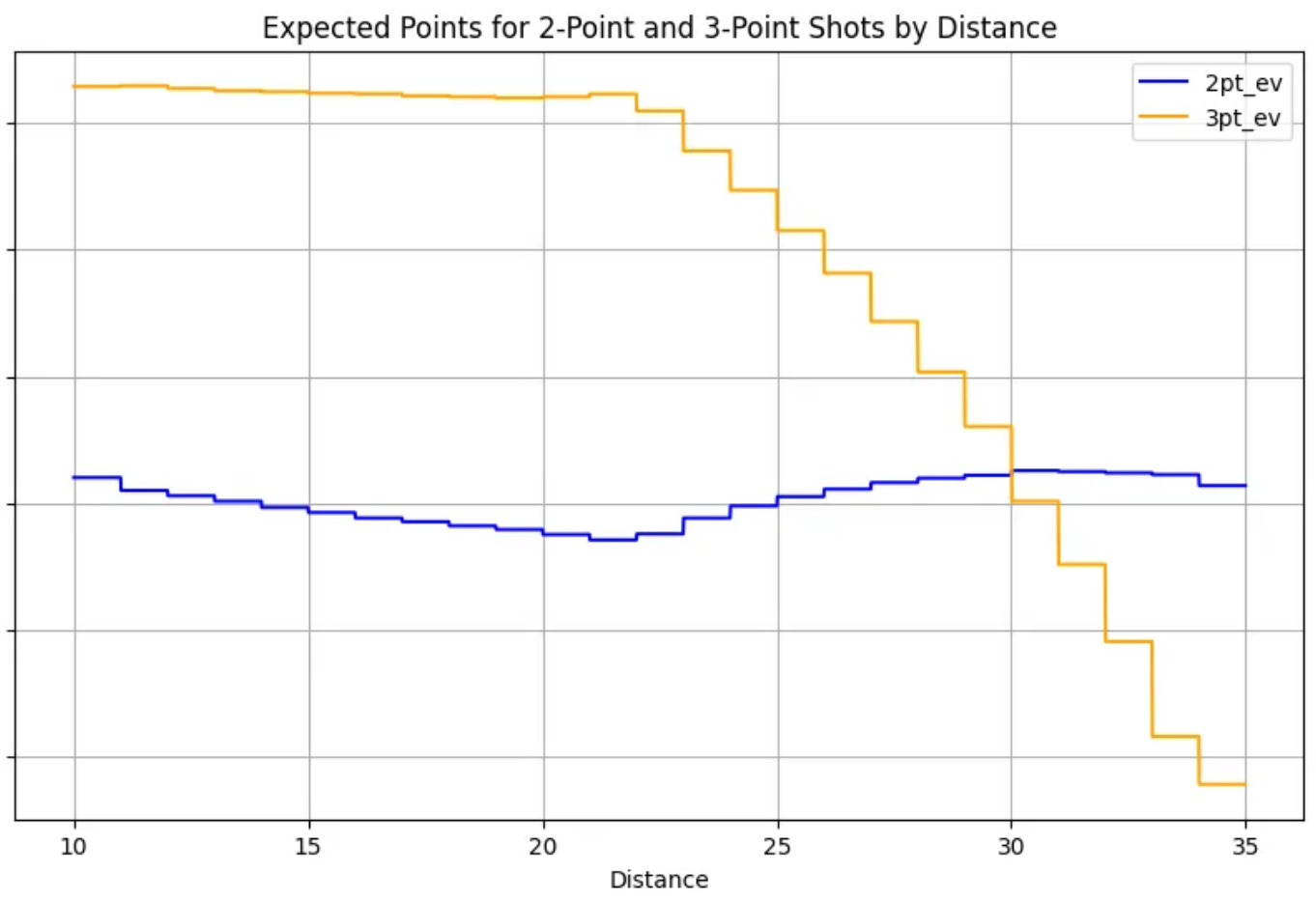

I decided to see what would happen if I tried to calculate the expected value of these shots.

Methodology:

This project has been done before but on the 2014 season, which is a little early and does not accurately capture what is taking place in the NBA right now.

The methodology behind the project is rather simple - I found play by play data from the 2019-20 NBA Season1, processed the dataset to include a Shot Type Value column by extracting from the play type. I then calculated Field Goal percentages for each distance.

For reference, the current 3-point line is positioned 23.75 feet from the rim along the arc and 22 feet from the rim in the corners.

Beyond that, I found an expected value at each distance, and there were some weird outliers, but I tried to account best by checking the trend before and after.

Honestly, not very encouraging. There is a point, roughly at 29 feet, where the expected value intersects. Just a few years earlier, the number of jump-shots taken from farther than 27 feet was too small to even sample, so this is a remarkable turnaround which made me realize that this exercise might be too difficult to accurately predict.

The Loophole:

For one thing, the percentage of 3 point shots made from 27-30 feet away is skewed by good shooters. If a wider variety of shooters were shooting from here, this would make the expected value fall.

I then thought about whether attacking the problem at the core could be a more feasible solution. Rather than find the distance with the closest expected value, why not just change the expected value itself? I decided to test out the shot types with two pointers equal to three and three pointers equal to four.

This is much more interesting - by changing the ratio from 2:3 to 3:4, we have a much more even graph. However, the expected value for three pointers still roughly beat the midrange shot, so if Daryl Morey ran my franchise in this fantasy land, he would still end up playing Microball.

What about 4:5?

I liked this one more - the three pointer is matches value with reasonable midrange shots, and even between long twos and threes, there isn’t such a large difference in expected value. An open long mid-range could reasonably match expected value of a lightly contested three. So how could the NBA do this? We could make each free throw worth two points, and then apply this scaling score on all past players - which works out well given most were playing in an era that encouraged this type of shot diet.

Conclusion:

Dean’s Substack highlights why this might do the game some good - bringing different styles because not every players needs to be a shooter.

There’s nothing wrong with the concept of shooting from farther for extra points - in fact, I would even call it a smart solution for boring and overly physical basketball. I can’t say I despise the way teams play today, but I can see the downsides to losing some of the defensive-oriented specialists because they can’t shoot.

I wouldn’t directly advocate for my change because of the problems with implementing it, but I do think it’s robust in conquering the issue at hand.

If you enjoyed this content, please subscribe! I post pretty often and don’t paywall anything.

It is important to note that during the 2019-20, the best volume sharpshooters were shooting significantly more(some 5x) from deep(28+ feet) than they did 6 seasons before.

The NBA should limit them to 33 a game!